On the Importance of Naming: Model Naming Conventions (Part 1)

💾 This article is for anyone who has ever questioned the sanity of a date not in ISO 8601 format

Have you ever been assigned to add new fields or concepts to an existing set of models and wondered:

-

Why are there multiple models named almost the same but slightly different?

-

Which model has the fields I need?

-

Which model is upstream or downstream from which?

- If I am going to add to those models, should I add it here or there (or over there)?

Someone on the data team might send you a list of models and say "It is in one of these models, but I am not sure which"

* users

* user_dimensions

* user_properties

* dim_users_attributed

* dim_users_revenue_attributed

This is a common problem when multiple developers (both past and present) are cohabitating in a project repo, continually creating new combinations of models in all directions as new analytic opportunities arise.

It's not difficult to imagine why this happens — people have different opinions, habits, and diligence about naming and when developing, it is often easier to build a new thing fit for the new purpose then to integrate your changes into the pre-existing ecosystem, test that yours works without breaking everyone else's, etc.

It is a common joke in computer science (and by extension data) that among all of the hard things we do, naming things is one of the hardest. These problems are not going away, but what if we can add a little more structure to the naming conventions so that the name of the model can clearly communicate its intent. Simply by reading the name of the model you can know what type of data might be in there, where in the DAG it might be (left, middle, right), or whether it is an internal building block or an external tableIn simplest terms, a table is the direct storage of data in rows and columns. Think excel sheet with raw values in each of the cells. used in the BI Tool for analysis.

This is the first in a series of posts around model naming conventions: why they are important and how you should think about naming models in your own projects.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

There is some prior art on this topic - the foundational post How We Structure Our dbt Projects. This article has helped countless projects begin the process of organizing their data, but after implementing dbt at a series of large enterprise companies it has left me with some lingering questions and some of its precepts are open to individual interpretations - which can cause drift and tech debt down the line.

I am elated to stand on the shoulders of giants to write a follow up to this post, with the caveat that this is aimed at a different audience. The above discourse is usually read or linked in 101 courses, where the focus is on initial project setup. In this series of posts you will see how our approach has shifted after working with and implementing these practices at scale.

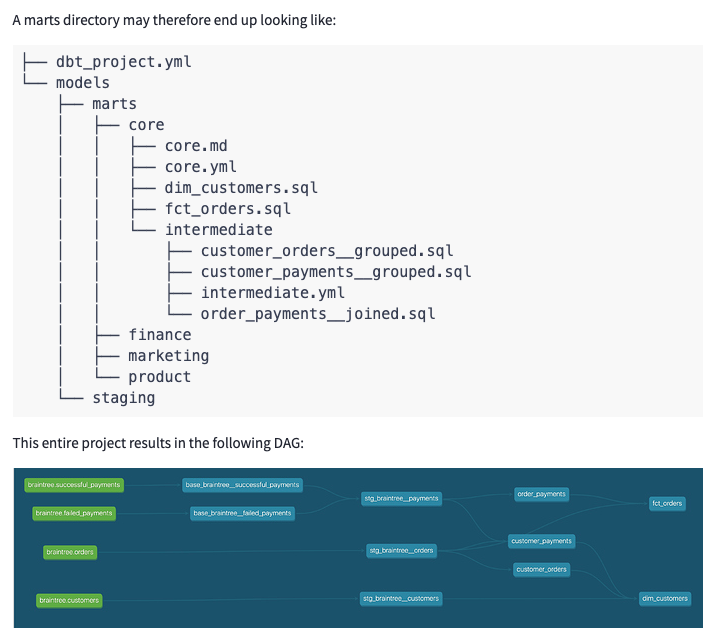

If you follow the advice from ‘How We Structure Our dbt Projects', you will end up with a project which is fairly easy to read when viewing within the folder hierarchy (from the Analytics Engineer perspective), but the same is not true when viewing in the DAG or the database itself. For the analyst or stakeholder who simply has access to the output database objects and not the hierarchy and flow with which they were developed, it can be at best slightly overwhelming, and at worst, unmanageable. With that in mind, I set out to help answer some of the outstanding questions around model naming and organization:

-

Do intermediates live within marts folder or as a top level directory (or does it matter)?

-

How can we delineate between what is a building block and what is a final output model?

-

We all (I think) agree on

stg_model naming conventions, but should we have more formalized naming guidelines as we move throughout the DAG??

The folder structure is a useful way to organize a project based off of your stakeholders and how they might contribute, as marts are usually mapped to specific business units. This structure also helps with configs, materializations, etc. which can be setup based on the folder structure, which is a great way to apply many configs all at once. But while it is great to have a project that makes sense when viewed from within the folder hierarchy of your dbt project, there are many other ways you and your team will be interacting with your models. By settling on a more formalized naming convention to supplement your folder based organization, your project will be much more usable when viewed in the DAG, in your database, or even in the BI layer

When your company scales to have hundreds or thousands of models, the subtle freedom to name models whatever you want starts to wreak havoc on the system — the developer isn't sure which model to add to or what it's usage is, so they start spinning up tangentially related models using some of the pieces and adding another slightly different variant of the, for example, users model. We should do a favor to others in our organization, including our future selves, by sensibly naming and keeping a lid on maintainability, preventing our DAG from descending into chaos.

Backing up, dbt builds a directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on the interdepencies between models – each node of the graph represents a model, and edges between the nodes are defined by ref functions, where a model specified in a ref function is recognized as a predecessor of the current model. Analytics Engineers often use the DAG to get a holistic tableIn simplest terms, a table is the direct storage of data in rows and columns. Think excel sheet with raw values in each of the cells. of the project or at least the subset of models that our model of interest is interacting with, typically a few models in either direction that are direct parents or children. The DAG helps you visualize how the data flows from left to right (from raw to transformed), without having to comb through SQL with a magnifying glass.

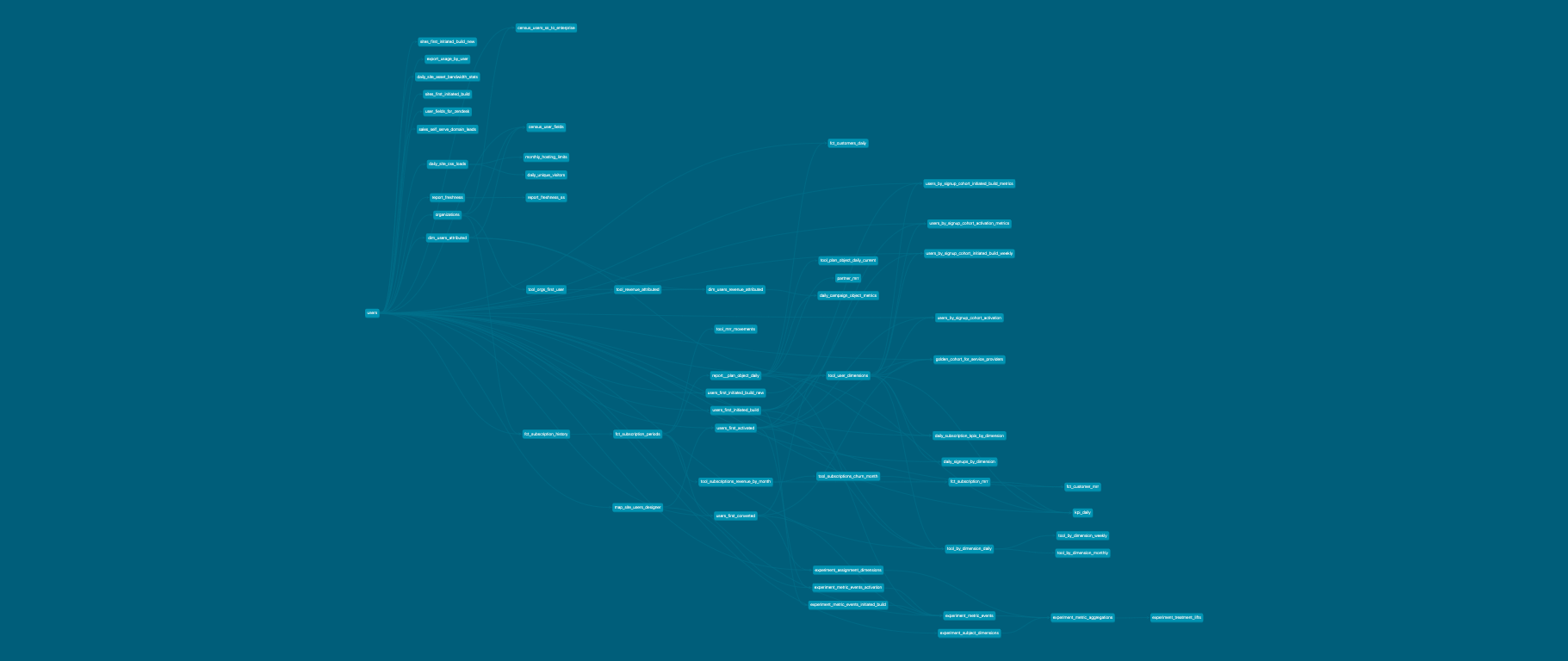

Here are some real life examples of a company's DAG, simplified using model selection syntax:

Let’s take a look at a real life example of an (admittedly rather complex) DAG to see just how important it is to have a solid framework for naming your models

+users

-

Everything to the left of their users flow

-

Meaning, all the descendants needed to build the

usersmodel

users+

-

Everything to the right of their users flow

-

Meaning, all the ancestor references that depend on the

usersmodel once created

Imagine trying to mentally internalize this after reading through countless SQL files, without looking at the DAG!

Zoom in and it will make more sense?

You're not actually supposed to be able to read those DAGs, as they are notoriously hard to grok when zoomed out. Let's pick a random zoom in point to show the "spider web", aka uncontrollable references to other models with no clear movement from left to right in a logical fashion.

In my utopia, when you zoom into a DAG and you would see a swimlane, or etymology, such that you would be able to understand the purpose of a given model. This real world example gives us a view into what happens when we don’t have that.

-

fct_'s on both sides of the screenshot, with all sorts of other models in between -

a

report_is used, not as an endpoint, but instead as an input by another model -

what is a

tool_(or your company’s equivalent of an undocumented pattern)? -

Does

user_at the beginning have a meaning?

In the organization which produced the above example, they are managing to remain prolific in their creation of models and outgoing analysis (which is good!), but they are introducing tech debt and potential failure modes that loom in the future, such as decreasing modularity and reproducibility, and increasing complexity. These are the kinds of issues that will increase the time to onboard new team members.

Hopefully by now I have convinced you that it is worth your time to spend a considerable amount of effort on a logical naming convention for your models. After all, if you cannot understand the flow of data through models even when looking at the DAG (or using folder hierarchy) then how are we supposed to set our company up for success, onboard new members to our team quickly, and ensure that without supervision, your project (and DAG) continues to grow in a stable fashion?

In the next posts in this series, I’ll walk you through a number of guidelines and heuristics that we have developed to make it easy and repeatable to name your models well.

Comments